War objectors' graffiti must be saved

May 13, 2016 11:02:15 GMT

sɐǝpı ɟo uoıʇɐɹǝpǝɟ, redneck, and 2 more like this

Post by IggyWiggy on May 13, 2016 11:02:15 GMT

In 1916 a conscientious objector, condemned by a tribunal for refusing to serve in the first world war, took up a pencil and very neatly explained his plight on the whitewashed wall of his cell in Richmond Castle in Yorkshire.

“‘I Percy F Goldsbrough of Mirfield was brought up from Pontefract on Friday August 11 1916 and put in this cell for refusing to be made into a soldier,” he wrote.

English Heritage, which now cares for the beautiful medieval castle, will launch a project on Friday to record, research and preserve the fragile walls that became a unique archive of rare first-hand testimonial from men who refused to join the war, as well as thousands of other inscriptions added later.

Kevin Booth, an archaeologist who is leading the project, groaned as he entered a cell with a shower of fresh white paint flakes on the floor. The first urgent challenge is to stop leaks in the stone roof above, through which water has been seeping for 150 years. “It is absolutely astonishing that so many of these have survived for a century, but they are now as fragile as cobwebs – this is the last last chance to save, if we can, or at least record them,” he said.

Goldsbrough was one of many conscientious objectors imprisoned in a 19th-century block house, chill even on a warm spring day, originally built against the castle’s great Norman keep as a place to lock up drunken or insubordinate soldiers from the barracks.

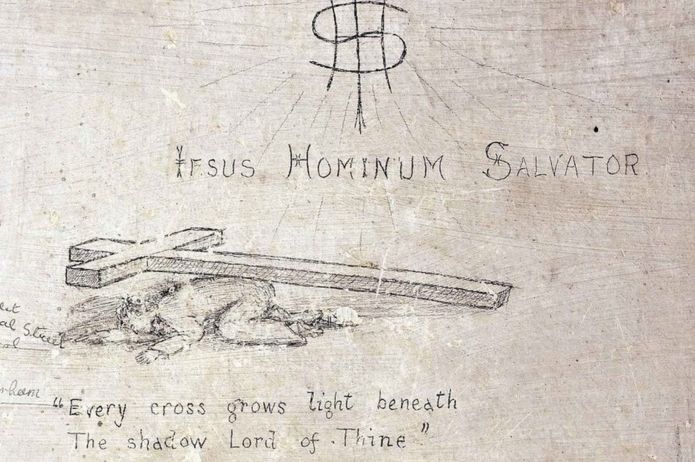

They included Quakers, Methodists who wrote hymns on the wall, Socialists who added the words and music of The Red Flag, and a lace maker who contributed a delicate pattern for a flowery border. There are drawings of mothers, girlfriends and familiar landscapes their creators must have wondered whether they would ever see again.

“The only War which is worth fighting is the Class War. The Working Class of this Country have no quarrel with the Working Class of Germany or any other Country. Socialism stands for Internationalism. If the workers of all countries united and refused to fight, there would be no war,” one prisoner wrote.

At Richmond the objectors refused to observe any military discipline or do any work that could contribute to the war effort – even declining to peel potatoes when they learned they would also feed the officers.

In 1916, some in the War Office were determined to make an example of the most obdurate, and 16 Richmond objectors were deported to a camp near Boulogne in France. When they refused an order to move ammunition, they were court-martialled and sentenced to death, later commuted to 10 years’ hard labour.

The block house continued to be used as a lockup for soldiers and, Booth believes, as a store and a useful shelter for people sloping off for a cigarette. The graffiti continued into the second world war and beyond. A Private Badger seems to have been locked up repeatedly, and left his name in almost every cell – he even changed the name of a charming sketch that Goldsbrough had drawn of his fiancee.

Booth is particularly interested in later graffiti that seems to respond to or comment on the earlier inscriptions. Above “Socialism: the Workers ONLY Salvation”, somebody wrote: “No my lad, work!!”

“Many of the later prisoners were serving soldiers, but it is striking that they do not damage or destroy the messages left by men whose views must have been so different,” Booth said.

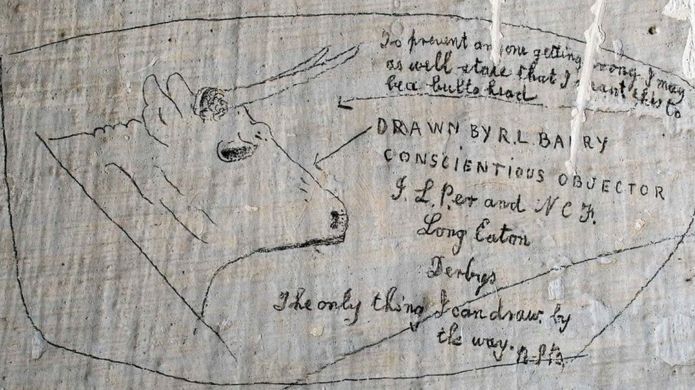

RL, one of the few identified prisoners – Richard Lewis Barry, a lace factory worker from Derbyshire – wrote in 1916: “You might as well try to dry a floor by throwing water on it, as try to end this war by fighting.” A 1939 writer, a soldier from the local regiment, added his initials a few inches away, but carefully preserved RL’s thoughts.

Among more than 5,000 drawings, poems and texts, Booth has some favourites. He believes one elaborate drawing must have been a first world war seascape of battleships, U-boats, biplanes and a zeppelin, to which later hands have added a handsome 1930s saloon car, a trawler, Spitfires, a bomb falling on a curving path, and a caricature of Hitler floating in the clouds. The ubiquitous Private Badger has rechristened one of the ships HMS Badger.

Volunteers will be recruited to record and catalogue the graffiti and identify as many of their authors as possible. The names and, occasionally, addresses of many women remain a puzzle to be solved. It is striking that, unlike other prison graffiti, there are no pin-up drawings or crude jokes.

Booth said interest in the conscientious objectors had been growing steadily in recent years. “The Richmond 16 has been the only story, but there is so much more in these walls.

“At the moment even our breath as we stand here is causing further damage. The public has been locked out of this building for more than 30 years, and I am desperate to get people back in. If we can just succeed in waterproofing the building and stabilising the atmosphere, that may soon become possible.”

www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/13/first-world-war-objectors-graffiti-project-richmond-castle