'Counterfeiting is an art'Joel Quispe sells his art for pennies on the dollar. Each masterpiece is roughly three feet long and two feet wide. Every print requires various types of ink and is meticulously designed and beautifully drawn. It is estimated that he has sold millions of dollars worth of his creations over the past five years – all while locked in a Peruvian prison while his family on the outside runs the show.

Quispe is a perfectionist who uses bonded paper, watermarks and gloriously intricate typography. He has proven a master at mass marketing, producing thousands of copies. He is also a criminal mastermind who distributes sheet after sheet of his specialty: fake US $100 bills.

Quispe is a master counterfeiter.

According to police investigators, Quispe is the de facto leader of one of the four (perhaps more) sophisticated counterfeiting operations operating out of Lima, Peru, which the US secret service has declared the world’s leading producer of counterfeit dollars.

“Since 2009, in our investigations with the secret service, we have seized about $75m in fake bills,” said Walter Escalante, head of the Peruvian national police’s anti-fraud division. “We don’t know what percentage entered the US illegally and has gone inside the financial system. We think that our $75m is the better part of what has entered the US.”

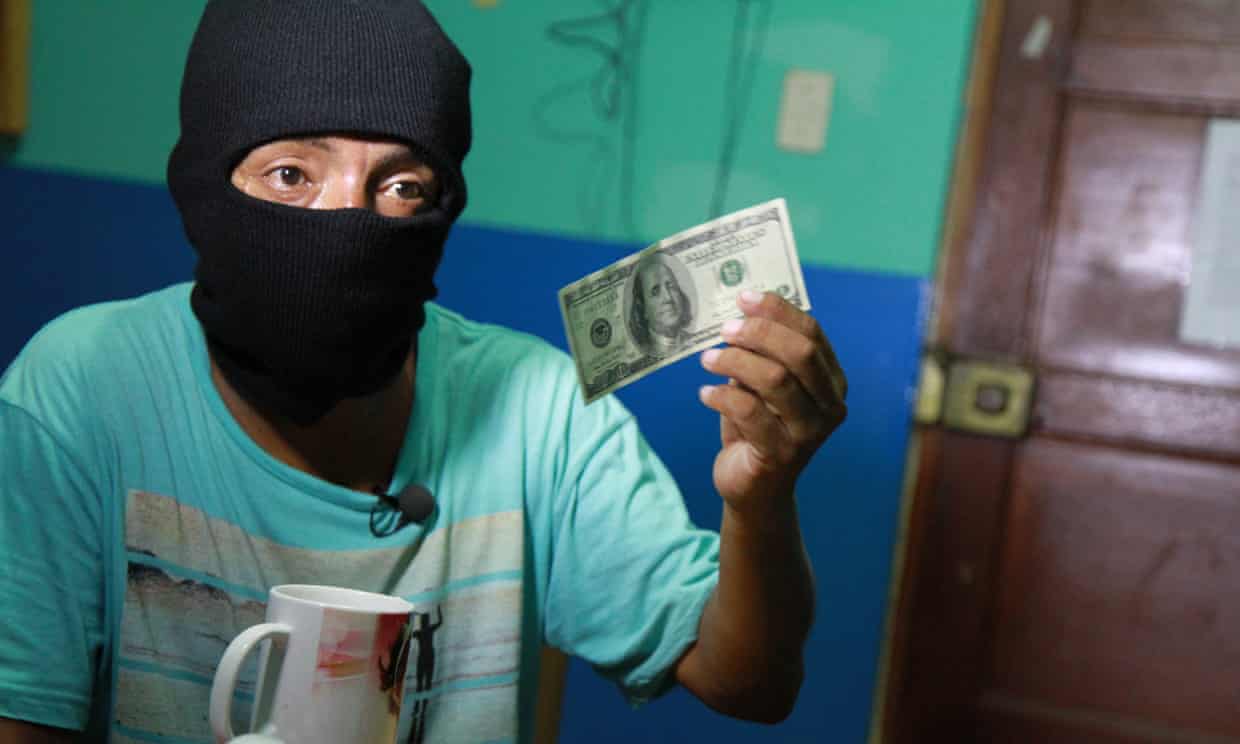

Criminals suggested that Escalante was unreasonably optimistic and the actual production of counterfeit dollars was far higher. In a clandestine meeting with the Guardian in a seedy hotel room in Lima, a veteran counterfeiter with over 20 years in the business detailed how his gang alone was producing an average of $3m to $5m in fake $100 bills every week.

“To make these bills, you need 10 to 12 people,” said Geraldo Chavez (not his real name), the counterfeiter. “One runs the machine, there is a designer, you have someone in charge of the supplies – the paper, the inks – you need someone to cut the bills, someone outside watching. The packer. At a minimum eight people, but usually eight to 12 people for the production to come out right.”

Asked how long it takes to fill an order for $5m, Chavez replied: “About a week. You make the design, then organize the paper and then start printing – pa! pa! pa!” He circled his hands in rotation, as he simulated the factory with six offset printing machines simultaneously pumping out money. “You have to work late in the night; the machines really make a lot of noise. That’s why they are up in the hills, in prefabricated houses, away from people.”

Workers are paid to thread security strips by hand into each bill. By soaking the bill, then inserting a needle, the counterfeiters add a final touch to make the fake bills appear authentic. Photograph: Jonathan Franklin for the Guardian

Chavez said the typical customer bought between $10,000 and$15,000, for which the buyer paid 20% of face value if they were a repeat customer or 25% if they were a newbie. “Once, we printed an order for $5m in fake bills for some Mexicans,” said Chavez.

Chavez pulled out a stack of freshly minted $100 bills. “These come from the north of Lima, where the factory is. Then they are brought to the center of Lima to enter the black market,” he added as he rubbed the bill with admiration. “They have a texture that is as close as you can get to a real bill. The finishing touches are of the highest quality. These are made to be sent abroad.”

Chavez went on to demonstrate the “finishing touches” by which a counterfeit bill is able to pass smoothly into circulation. The final steps were meant to improve the raised lettering, he said as he opened a small plastic bag of what looked like cocaine, but was in fact a type of flour. He mixed the flour with glue and water and stirred the mixture as if he were preparing instant coffee, careful to get an even consistency. He then used his finger to lightly paint certain parts of the bill with the glue mixture. The bills were then left to dry and will ultimately carry a rippled effect on key spots, similar to the texture of a real bill.

“The printer has to be skilled,” said Don Brewer, who spent 26 years with the US secret service and became head of the agency’s anti-counterfeiting division. “They need to be artistic and meticulous. Because offset begins by photographing the money, the negative is the key. But the negative fails to hold all the detail of the original, so it has to be touched up by hand. In many counterfeit plants we raided, we would find large negative blowups that were used to add detail.”

In the US and much of Europe, the sale, distribution, and use of offset printers are watched closely by anti-counterfeiting units. In Peru, however, the offset industry is a free-for-all. Entire neighborhoods are famous for being places to buy fake passports, bogus driver’s licenses, invented university degrees, false job contracts, forged housing deeds and practically anything else under the sun.

In Peru, awareness of fake currency is so high that retail shops regularly provide cashiers with hole punchers. When a fake bill is received, the cashier quickly pops out a few holes before curtly returning the bill to an oft-surprised client. Warning signs at the entrance to many pharmacies in Lima are plastered with fake bills punched full of holes and a sign explaining that any counterfeit bill received will be perforated on the spot.

The profits from this business are huge – roughly $600,000 a week for his gang alone, said Chavez. “The raw materials are very cheap. I will give you an example. A $100 bill that I sell for $20? My costs are between $3 and $5. So what’s my profit? $15. Here [in Peru], you get the supplies you need at a low cost. This glue? It costs me 50 cents. The flour, even less. All this?” he said, pointing to the material on the desk in front of him. “Not even a dollar. The paper you buy in bulk and that costs 40-50 sols [$10-$15 a stack].”

Competition is fierce, too. “If you have the best quality, people come to you,” said Chavez. “If it is second-rate? Doesn’t have the raised lettering? If the paper’s not right? If it doesn’t have the texture? They aren’t going to buy it. Nothing’s going down.”

“They try to make the minimum investment possible,” said Escalante, the Peruvian police commander. “It’s not in their best interest to use expensive materials. And you have to remember, these bills are going to the United States, and in the US the people have confidence in their bills. They don’t check as much.”

Peruvian counterfeiters are so creative that even worthless currencies are brought back to life. Thanks to the world’s highest inflation rate, the Venezuelan 10 Bolivar note has seen its value plummet over the past five years from roughly $5 to two cents. For Peruvian counterfeiters the Venezuelan currency is worth more than the money printed on it. They use the 10 Bolivar note as raw material to produce counterfeit bills.

First, the Peruvian gangs bleach off the portraits of both Guaicaipuro (a revered indigenous leader) and the harpy eagle and then print Benjamin Franklin’s stiff grimace onto the face of a newly minted $100 bill. “When people check those bills, the paper is right, it has many of the properties of a real bill,” explains Reimundo Urcia Bernabe, a 20-year veteran of the Peruvian police who, putting the bill under his microscope, can often detect the faint outlines of the now-erased Venezuelan currency.

“The Venezuelan bills have a lilac-colored security strip, while the US [security strip] is red and blue,” explains the retired police officer. “Because the paper is real, it passes many of the [forgery detection] tests, but if you look close, you can still read the word “diez” (ten) which has been reprinted with the words ‘one hundred’.”

According to the counterfeiters, every month millions of these fake dollars are smuggled out of Peru and into the US by cash couriers known as “burriers”. Flying out of Jorge Chávez international airport, the “burriers” secret the money inside hollowed out books, the soles of sneakers and inside picture frames. In one attempt, the smugglers filled a suitcase with Furbies, the children’s toys, each stuffed full of fake $100 bills.

“Most of the bills end up in the United States – they go through Mexico,” explained Chavez. “There are Peruvian-Mexicans who are in charge of passing the money over the border. You don’t [smuggle] by airplane [directly] into the United States because their airport control uses the latest technologies … These bills get into the US over the frontier by the coyotes. This is a mafia – they get the bills into Texas and California.”

In an attempt to break up the counterfeit gangs and reduce the flood of fake cash, the US secret service set up a regional office in Lima three years ago to work closely with Peruvian police. But infiltrating the gangs is difficult. The counterfeiters live and work in marginal neighborhoods where outsiders are instantly noticed and often unwelcome. For the Peruvian police, rampant corruption in the judiciary and among their peers makes the battle against counterfeiters a weary fight.

Hoping to disrupt the counterfeiters, the US Treasury has launched a seemingly endless string of redesigns to US currency, adding features both public and private to make the bills ever harder to copy. Given the leap in printing technologies, however, innovations are volleyed back and forth as the US government serves up a new round of holograms, floating ink and security strips, while the forgers fire back by reverse engineering those same features. It’s not a match likely to end anytime soon. “Every time a new design would come out, we would have an informal pool on how soon it would be counterfeited,” said retired agent Brewer.

Despite the flood of Peruvian-made fake bills entering into circulation, Brewer says the Peruvian bills never make it beyond the “retail” street level of commerce. Hi-tech magnetic ink allows counting machines at banks to instantly sort the authentic cash from the fake bills. “There is no counterfeit bill that I know of that will pass the scrutiny of the equipment used by banks worldwide. So in my opinion, it is not a threat to our banking system in that way. But the dollar stands for the integrity of the US and people everywhere depend on that.”

While police officials struggle to maintain an organized opposition to the flood of fake dollars, the counterfeiters continue to innovate. By coloring the bills with run-of-the-mill yellow highlighters, the criminals simulate “security fibers” that glow under ultraviolet counterfeit detection systems. Using tiny pushpins, the counterfeiters riddle their freshly minted bills with tiny holes giving the impression of raised lettering . “They are very good artists,” said Urcia.

Like many emerging artists, however, counterfeiters often have a huge ego and an unquenchable desire for recognition, according to police investigators.

“I used to carry on about how good their product was and what a genius they were, and they would throw caution right out the window and ignore any suspicion,” said Brewer. “Counterfeiters are proud of their work, and I can’t tell you how useful that is when doing undercover work.”

Peruvian counterfeiter ‘Geraldo Chavez’ demonstrates the finishing touches to a fake bill. Photograph: Jonathan Franklin for the Guardian

Additional reporting by Dan Collyns

www.theguardian.com/world/2016/mar/31/counterfeiting-peruvian-gang-fabricating-fake-100-bills